Home | Biodata | Biography | Photo Gallery | Publications | Tributes

Indus Script

|

Home | Biodata | Biography | Photo Gallery | Publications | Tributes Indus Script |

|

INTRODUCTION

Scholars in India and abroad have held differing views about the Indus writings. Claims of decipherments1,2 have been made and heated debates have followed.

It looks as though the script cannot be deciphered until bilingual writings are found. However, structural analysis of undeciphered texts can be made even when the contents of the texts remain a mystery.3 Such an analysis is made possible by the availability of two computerized concordances , one compiled by Asko Parpola4 in Finland and the other by Iravatham Mahadevan5 in India.

In our earlier studies, we have made use of the tables contained in the Indian concordance to cluster the frequently occurring Indus signs on the basis of their positional characteristics6, to study the possibility of segmenting long Indus texts into shorter texts on the basis of an objective criterion7, and to examine whether the proximity between two signs forming a pair could be attributed to chance or not8.

In an earlier study9 one of us has discussed the most frequently occurring Indus inscriptions with reference to the sites in which they occur. The main aim was to find out whether there are oft repeated inscriptions which are found in only certain sites and whether there are also common inscriptions which are found in more than one site.

The study was motivated by the expectation that the name of the place, the name of a king or the most influential person and/or group of the region, the name of deities, titles of officials, characteristic merchandise and other information can be found in the frequently occurring inscriptions of a place. In this paper we go a step further and study whether any information specific to a particular site can be obtained by examining the frequency of occurrence of sign in each site. For this purpose we make use of the method we developed to study the association between two signs that occur next to each other.

2. MEASUREMENT OF AFFINITY AND ANTIAFFINITY

There is no universal agreement on what a given sign represents. It can be a letter or a syllable or any one or more of the other categories. It is quite possible that a single sign may have more than one connotation in the same line of a text. Considering the number of individual signs and their functional and positional characteristics, Mahadevan10 has concluded that the Indus script is not alphabetic or quasi-alphabetic. The Soviet scholars11, who have segmented the Indus texts into blocks of words and word combinations have judged from the length of the blocks that the Indus writings are morphemic-syllabic. Other scholars have used other criteria to decide upon the nature of the Indus signs. In our works we need not make any specific assumption about the nature of the signs.

Out of the 13,372 signs recorded in the concordance 55.4% are from Mohenjodaro, 32.6% from Harappa, 5.7% from Lothal, 3.2% from Kalibangan, 2.3% from Chanhudaro. West Asia and other sites account for the remaining occurrences. Any sign whose occurrence is independent of the region or site would occur at different sites in the same kind of proportion. For instance, the sign which the Soviet scholars interpret as

per (meaning 'great') occurs 59.1%, in

Mohenjodaro, 34.1% in Harappa, 2.3% in Lothal, 2.3% in Kalibangan and 0.8% in

Chanhudaro. We can see that the distribution of this sign over the sites does not differ greatly from the overall distribution of signs. Thus one can conclude that this sign is not likely to be of any local significance in any region. On the other hand, the HARROW sign (![]() ), which

Mahadevan12 considers as a secondary nominal suffix, has the following distributions 28.5% in Mohenjodaro, 67.3% in Harappa, 0.3% in Lothal, 2.5% in Kalibangan, and 0.9% in Chanhudaro. The difference between the distribution of this sign and the overall distribution of signs is particularly striking. Over one-half of the signs have been recorded in Mohenjodaro but less than one-third of the occurrences of this sign have been observed there. On the contrary, Harappa accounts for less than one-third of the signs but its share in the occurrence of this sign is more than two-thirds. Hence we conclude that the unexpectedly frequent occurrence of the HARROW sign in Harappa is not merely due to chance.

), which

Mahadevan12 considers as a secondary nominal suffix, has the following distributions 28.5% in Mohenjodaro, 67.3% in Harappa, 0.3% in Lothal, 2.5% in Kalibangan, and 0.9% in Chanhudaro. The difference between the distribution of this sign and the overall distribution of signs is particularly striking. Over one-half of the signs have been recorded in Mohenjodaro but less than one-third of the occurrences of this sign have been observed there. On the contrary, Harappa accounts for less than one-third of the signs but its share in the occurrence of this sign is more than two-thirds. Hence we conclude that the unexpectedly frequent occurrence of the HARROW sign in Harappa is not merely due to chance.

In general, how do we measure this association between a sign and a site? It should have been obvious by now that the frequency of occurrence of a sign in a site

per se is not sufficient to measure the kind of association we seek to

discover. To use a statistical term, we need the theoretical (or expected) frequency. It is the frequency that one would expect if the distribution of the sign conforms to the overall distribution of signs. For instance, the sign ![]() occurs 132 times. Had it been distributed the same way as the total of all signs, we would have observed 72 occurrences in Mohenjodaro, 43 in Harappa, 8 in Lothal, 4 in Kalibangan and 3 in Chanhudaro. If we set up the hypothesis that the sign is independent of the regions, then this is the distribution we would expect. Any deviation from this theoretical frequency can be considered as error (with respect to the hypothesis). We have developed a procedure to test how serious the error is for each sign in each site. It leads to the construction of an index, which has a maximum value of 100 when there is more than 99% chance that the more frequent occurrence of a sign in a site is not due to chance. The minimum value is

--100 when there is more than 99% chance that the less frequent occurrence of a sign in a site is not due to chance (Further details of the procedure can be found in our earlier

paper8 on pairs of Harappan signs). If a sign has a highly positive value for its index in a site, we can say that there is affinity between the sign and the site. On the other hand, if a sign has a highly negative value for its index, it indicates that there is anti-affinity between the sign and the site. In case the numerical value of the index is rather low, it can be concluded that the sign has an independent position in that region. Some examples are presented in Figure 1.

occurs 132 times. Had it been distributed the same way as the total of all signs, we would have observed 72 occurrences in Mohenjodaro, 43 in Harappa, 8 in Lothal, 4 in Kalibangan and 3 in Chanhudaro. If we set up the hypothesis that the sign is independent of the regions, then this is the distribution we would expect. Any deviation from this theoretical frequency can be considered as error (with respect to the hypothesis). We have developed a procedure to test how serious the error is for each sign in each site. It leads to the construction of an index, which has a maximum value of 100 when there is more than 99% chance that the more frequent occurrence of a sign in a site is not due to chance. The minimum value is

--100 when there is more than 99% chance that the less frequent occurrence of a sign in a site is not due to chance (Further details of the procedure can be found in our earlier

paper8 on pairs of Harappan signs). If a sign has a highly positive value for its index in a site, we can say that there is affinity between the sign and the site. On the other hand, if a sign has a highly negative value for its index, it indicates that there is anti-affinity between the sign and the site. In case the numerical value of the index is rather low, it can be concluded that the sign has an independent position in that region. Some examples are presented in Figure 1.

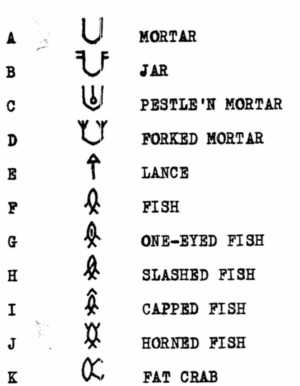

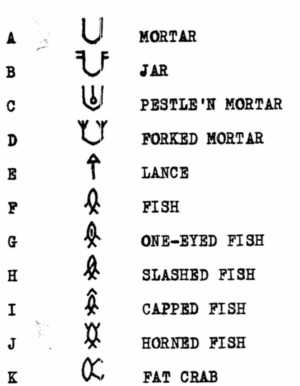

3. ASSOCIATION BETWEEN SIGNS AND CITIES

In this paper we consider 67 signs, each of which occurs more than fifty times. How frequently each of these signs occurs in each of the Harappan sites is given in the concordance. We briefly discuss here the association of certain signs with five major Harappan sites, viz., Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Lothal, Kalibangan, and Chanhudaro (The other sites are not considered, since they account for less than 2% of the occurrences). A more detailed list is given in Figure 2.

3.1 MOHENJODARO

Mohenjodaro is on the western bank of Indus river in Pakistan and it is about 300 kms from Jaisalmer. The largest of all the Indus sites, it is spread over 500 acres.

We note that the sign ![]() is positively associated with Mohenjodaro. While discussing a text that occurs 59 times in Mohenjodaro,

Siromoney9 has pointed out

is positively associated with Mohenjodaro. While discussing a text that occurs 59 times in Mohenjodaro,

Siromoney9 has pointed out ![]()

![]()

![]() is a portion peculiar to

Mohenjodaro. It occurs 24 times there, either as a complete inscription or as part of a longer inscription in the terminal

position.This combination does not occur in any other centre.

is a portion peculiar to

Mohenjodaro. It occurs 24 times there, either as a complete inscription or as part of a longer inscription in the terminal

position.This combination does not occur in any other centre.

Besides, the pair ![]()

![]() occurs in a total of 70 inscriptions. Mohenjodaro accounts for 60 of these occurrences. We may mention that the Soviet scholars have given the phonetic value

kanta (meaning 'hero' ) to this pair. We see that the sign

occurs in a total of 70 inscriptions. Mohenjodaro accounts for 60 of these occurrences. We may mention that the Soviet scholars have given the phonetic value

kanta (meaning 'hero' ) to this pair. We see that the sign ![]() has negative association with all the other sites, except for Lothal , where it is recorded 15 times when it is expected to occur only about 12 times. Also, the other sign in this portion

has negative association with all the other sites, except for Lothal , where it is recorded 15 times when it is expected to occur only about 12 times. Also, the other sign in this portion ![]() has negative association with all the other sites without exception. This reinforces our belief that whatever message this portion conveys is important specifically to Mohenjodaro sign.

has negative association with all the other sites without exception. This reinforces our belief that whatever message this portion conveys is important specifically to Mohenjodaro sign.

It is interesting to note the independence of the JAR (![]() ) in Harappa. It occurs 766 times here while it is expected to occur 767 times. The agreement is remarkably close. Another sign which has neither positive nor negative association with Mohenjodaro is

) in Harappa. It occurs 766 times here while it is expected to occur 767 times. The agreement is remarkably close. Another sign which has neither positive nor negative association with Mohenjodaro is ![]() which

Mahadevan13 considers to have 'great cultural significance for proving the existence of the plough in the Proto-Indian civilization and the connection between the Sumerian and the Proto-Indian

scripts'. Rejecting the phonetic value uravar (from uru, to plough) suggested by Heras and the value

meti (from meti - plough) proposed by the Finnish scholars, Mahadevan tentatively interpreted the sign to stand for

cer

(meaning 'granary' ).

which

Mahadevan13 considers to have 'great cultural significance for proving the existence of the plough in the Proto-Indian civilization and the connection between the Sumerian and the Proto-Indian

scripts'. Rejecting the phonetic value uravar (from uru, to plough) suggested by Heras and the value

meti (from meti - plough) proposed by the Finnish scholars, Mahadevan tentatively interpreted the sign to stand for

cer

(meaning 'granary' ).

While the JAR sign is independent, the HARROW sign, which also occurs frequently in the terminal position has significant negative association with Mohenjodaro.

3.2 HARAPPA

Harappa is situated on the bank of river Ravi about 200 kms southwest of Lahore in Pakistan. Geographically, the closest major Indian site is Kalibangan in Rajasthan.

The HARROW sign and the sign ![]() have affinity with Harappa. Another sign with a similar characteristic is JAR. It occurs 472 times against the expected occurrences of 447. Thus the index works out to 77. It is interesting to note that the combination

have affinity with Harappa. Another sign with a similar characteristic is JAR. It occurs 472 times against the expected occurrences of 447. Thus the index works out to 77. It is interesting to note that the combination ![]()

![]()

![]() occurs 40 times

in Harappa, once in Mohenjodaro and never in any other site. Most often it occurs as the first line of a two-line text, the second line being

occurs 40 times

in Harappa, once in Mohenjodaro and never in any other site. Most often it occurs as the first line of a two-line text, the second line being ![]() followed by a

numeral. It is significant that the sign

followed by a

numeral. It is significant that the sign ![]() occurs nine times out of ten at Harappa and that the numeral

occurs nine times out of ten at Harappa and that the numeral ![]() occurs 58 out of 64 times at Harappa (it occurs in the pair

occurs 58 out of 64 times at Harappa (it occurs in the pair ![]()

![]() ). The two-line inscription is neither a seal nor a sealing but is entered in the concordance as miniature tablet without any field symbol.

). The two-line inscription is neither a seal nor a sealing but is entered in the concordance as miniature tablet without any field symbol.

The LANCE sign (![]() ) which Mahadevan10 considers as a functional twin of the JAR sign, has no strong relationship with Harappa one way or the other. It is expected to occur 73 times and it occurs 74 times. Mahadevan suggested that it was employed as an ideogram representing a

'warrior' while the ideographic meaning he proposed for the JAR sign is

'priest'. It seems that while Harappa accounted for its proportionate share of warriors, it had made more frequent references to priests than one would expect. We may also mention that the sign that the Russian

scholars11 take to stand for 'warrior' is not LANCE but MAN (

) which Mahadevan10 considers as a functional twin of the JAR sign, has no strong relationship with Harappa one way or the other. It is expected to occur 73 times and it occurs 74 times. Mahadevan suggested that it was employed as an ideogram representing a

'warrior' while the ideographic meaning he proposed for the JAR sign is

'priest'. It seems that while Harappa accounted for its proportionate share of warriors, it had made more frequent references to priests than one would expect. We may also mention that the sign that the Russian

scholars11 take to stand for 'warrior' is not LANCE but MAN (![]() ) which has high negative association with Harappa (incidentally, Mahadevan interprets this sign to be an ideogram representing a

'servant' ).

) which has high negative association with Harappa (incidentally, Mahadevan interprets this sign to be an ideogram representing a

'servant' ).

It is interesting to note that the signs, which have highly positive association with Mohenjodaro, are negatively associated with Harappa. We shall presently discuss this dissimilarity between the two cities, which are the largest cities of the Indus valley civilization.

3.3 Lothal

Unlike Mohenjodaro and Harappa, Lothal is close to the sea and it is a major Indian site. The most noteworthy feature of this town is its careful planning and efficient execution with utmost precision14.

The sign ![]() , which has already been discussed has high affinity with Lothal. The signs

, which has already been discussed has high affinity with Lothal. The signs ![]() and

and ![]() are also positively associated with this site. But the combination

are also positively associated with this site. But the combination ![]()

![]() which is the most frequently occurring pair in the Indus writings does not seem to have any specific relationship, with any one particular site.

which is the most frequently occurring pair in the Indus writings does not seem to have any specific relationship, with any one particular site.

Of the two CRAB signs, ![]() has positive association with Lothal, while

has positive association with Lothal, while ![]() is negatively associated. In an earlier

paper8, we have argued that the two signs cannot be taken to be mutually substitutable.

is negatively associated. In an earlier

paper8, we have argued that the two signs cannot be taken to be mutually substitutable.

The three most frequently occurring terminal signs namely JAR, HARROW and LANCE have negative association with Lothal.

3.4 KALIBANGAN

Kalibangan is in Rajasthan on the bank of a dried-up river about 750 kms north of Lothal.

The most frequently occurring sign in Kalibangan is the JAR. It is not quite useful in that it occurs 44 times, while it is expected to occur 42 times. The other two signs which occurs very frequently are ![]() (33 times against the theoretical frequency of 19) and

(33 times against the theoretical frequency of 19) and ![]() (21 times against the theoretical frequency of 4). Of these two, the unusual occurrence of MAN sign is worth noting, since it occurs five times more often than expected. What makes it more interesting is that eight sealings have been discovered in Kalibangan with a fairly long inscription

(21 times against the theoretical frequency of 4). Of these two, the unusual occurrence of MAN sign is worth noting, since it occurs five times more often than expected. What makes it more interesting is that eight sealings have been discovered in Kalibangan with a fairly long inscription ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() . This inscription is not found in any other site. Even the pair

. This inscription is not found in any other site. Even the pair ![]()

![]() occurs only 14 times, all sites taken together.

occurs only 14 times, all sites taken together.

Mahadevan10 has discussed the JAR and BEARER (![]() ) signs

as motifs and concluded that the BEARER sign may denote an officer, while the JAR-BEARER sign (

) signs

as motifs and concluded that the BEARER sign may denote an officer, while the JAR-BEARER sign (![]() ) may indicate an officer with priestly duties. It is interesting to observe that the

BEARER has received his fair share of references, while the JAR-BEARER has not been mentioned in the inscriptions as often as one would expect.

) may indicate an officer with priestly duties. It is interesting to observe that the

BEARER has received his fair share of references, while the JAR-BEARER has not been mentioned in the inscriptions as often as one would expect.

3.5 Chanhudaro

Chanhudaro is located on the eastern bank of Indus river in India. It is about 100 kms from Mohenjodaro. It accounts for only 2 percent of the signs recorded in the concordance.

Except for ![]() , all other FISH signs included in the analysis occur more often in Chanhudaro than what could be expected. Most of the signs occur about as often as the overall distribution of signs would warrant.

, all other FISH signs included in the analysis occur more often in Chanhudaro than what could be expected. Most of the signs occur about as often as the overall distribution of signs would warrant.

4. SIMILARITY BETWEEN HARAPPAN SITES

We have already observed that some signs which have a high degree of affinity with Mohenjodaro have a high degree of antiaffinity with Harappa. This comparison is made only on the basis of a few signs whose association with both cities are high, whether positive or negative. If we take all the 67 signs into account and compare the sites in terms of the affinity of different signs to them we may see the similarity or the difference between the sites. With this purpose in mind, we have defined a measure of similarity between every pair of sites in such a way that it ranges from 0 to 100. Two sites will have a high value of similarity if the signs exhibit the same kind of association with both the sites. Similarly, two sites will have a low value of similarity, if the sites differ radically in their association with different signs. The values of similarity are given in Figure 3. We see that Mohenjodaro and Harappa are least similar. The measure of similarity between them is as low as 4. On the other hand, the similarity is highest between Mohenjodaro and Lothal. In this case, the measure works out to 70.

The sites can be clustered on the basis of the similarity between any two sites. The result is presented in the form of a tree diagram in Figure 4. We observe that Mohenjodaro and Lothal are closest to each other. Of all the remaining sites, Chanhudaro is the one which comes closest to this cluster. Next in the order of homogeneity is Kalibangan. Harappa stands apart from all these sites. It will be interesting to study the peculiarity of Harappa in this respect.

CONCLUSION

In this paper, we have considered 67 signs, each of which occurs at least fifty times in the Harappan inscriptions. A procedure has been developed to contrast the distribution of each sign in each of the major Harappan sites with the overall distribution of Harappan signs. To facilitate the comparison, we have defined an index of affinity that measures the association between Harappan signs and sites. The processing of the data was carried out on IBM 370/155 computer at the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras.

A similar analysis can be made to measure the association between Harappan signs and the field symbols associated with them. Also, the method can be used to study the occurrences of pair wise combinations of Harappan signs in different sites. These and other problems are being analysed as part of a larger project.

We wish to thank our colleagues Dr S. Govindaraju, Dr R. Chandrasekaran and Mr L. Durai Pandian and our student Mr D. Suresh for their help in the preparation of this paper.

REFERENCES

1. S.R. Rao, The Decipherment of the Indus Script, Asia Publishing House, Bombay, 1982.

2. M.V.N. Krishna Rao, Indus Script Deciphered, Agam Kala Prakashan, New Delhi, 1982.

3. E.O.W Barber, Archaeological Decipherment, Princeton University Press, 1974.

4. A Parpola, S. Parpola and S Koskenniemi, Materials for the study of the Indus Script: A concordance

to the Indus Inscriptions, Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Helsinki, 1973.

5. Iravatham Mahadevan, The Indus Script; Texts, Concordance and Tables, Memoirs of Archaeological Survey of India, No.77, Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi, 1977.

6. Gift Siromoney and Abdul Huq, Cluster analysis of Indus signs; a Computer approach,

Proceedings of the

Fifth International Conference -- Seminar of Tamil Studies, M. Arunachalam (Ed.,) 1981.

7. Gift Siromoney and Abdul Huq, Segmentation of unusually long texts of Indus writings: a

mathematical approach, Journal of the Epigraphical Society of India, Vol. 9,1982,

pp.68-77.

8. Gift Siromoney and Abdul Huq, Measurement of affinity and antiaffinity between signs of the Indus script, STAT-49/83 (mimeo), Paper presented at the

Seminar on the Indus Script, Tamil University, Thanjavur, 1983.

9. Gift Siromoney, Classification of frequently occurring inscriptions of Indus civilization in relation to Metropolitan cities, STAT-45/80 (mimeo), Paper presented at the

Seventh Annual Congress of the Epigraphical Society of India, Calcutta, 1981.

10. Iravatharn Mahadevan, Terminal ideograms in the Indus script, Harappan

Civilization, Gregory L. Possehl, (ed.), Oxford and IBH Publishing Co, New Delhi, 1982.

11. Y.V. Knorozov, M.F. Albedil, B.Y. Volchok, Proto-Indica, 1979, Report on the investigation of the Proto- Indian Texts, Nauka

Publishing House, Central Department of Oriental Literature, Moscow, 1981.

12. Iravatharn Mahadevan, Towards a grammar of the Indus texts: '

intelligible to the eye, if not to the ears', Paper presented at the Seminar on Indus

Script, Tamil University, Thanjavur, 1983.

13. Iravatham Mahadevan, Dravidiari parallels in Proto-Indian script, Journal of Tamil

Studies, Vol. 2, 1970.

14. S.R. Rao, Lothal : A Harappan Port Town (1955-62), Vol.1, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of

India, New Delhi, 1979.

| MOHENJODARO | HARAPPA | ||||||

| S.No | Sign | Observed frequency | Theoretical frequency | Index | Observed frequency | Theoretical frequency | Index |

| 1 | 70 | 72.96 | -27 | 22 | 43.68 | -100 | |

| 2 | 40 | 28.86 | 96 | 12 | 17.28 | -80 | |

| 3 | 68 | 91.48 | -99 | 84 | 54.76 | 100 | |

| 4 | 205 | 207.45 | -14 | 122 | 124.19 | -16 | |

| 5 | 5 | 35.20 | -100 | 58 | 20.86 | 100 | |

| 6 | 78 | 71.87 | 53 | 45 | 43.03 | 24 | |

| 7 | 101 | 193.30 | -100 | 239 | 115.72 | 100 | |

| 8 | 130 | 123.60 | 44 | 74 | 74.00 | 0 | |

| 9 | 144 | 118.71 | 100 | 43 | 66.24 | -100 | |

| 10 | 40 | 39.75 | 3 | 19 | 23.80 | -67 | |

| 11 | 28 | 177.65 | -100 | 288 | 103.36 | 100 | |

| 12 | 766 | 767.25 | -4 | 472 | 446.40 | 77 | |

| Figure 1: Values of the index of affinity between some Harappan signs and sites. | |||||||

| Mohenjodaro | Lothal | Chanhudaro | Kalibangan | Harappa | |

| Mohenjodaro | 100 | 70 | 60 | 49 | 4 |

| Lothal | 70 | 100 | 65 | 64 | 18 |

| Chanhudaro | 60 | 65 | 100 | 67 | 32 |

| Kalibangan | 49 | 64 | 67 | 100 | 37 |

| Harappa | 4 | 18 | 32 | 37 | 100 |

| Figure 3: Similarity matrix of Harappan sites based on the overall affinity of each site with signs. | |||||

|

|